|

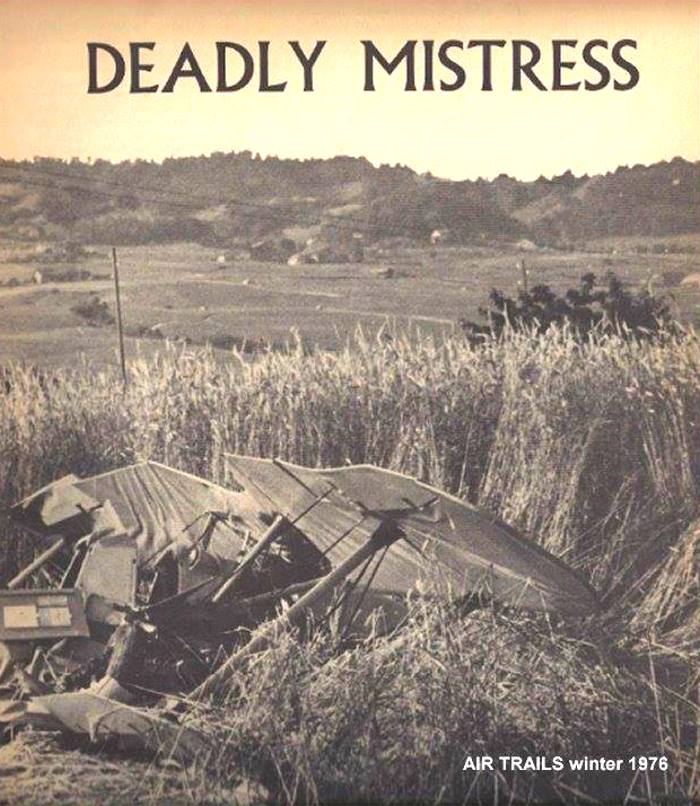

DEADLY MISTRESS The Story of my Airplane Crash June 24, 1961 |

|

DEADLY MISTRESS The Story of my Airplane Crash June 24, 1961

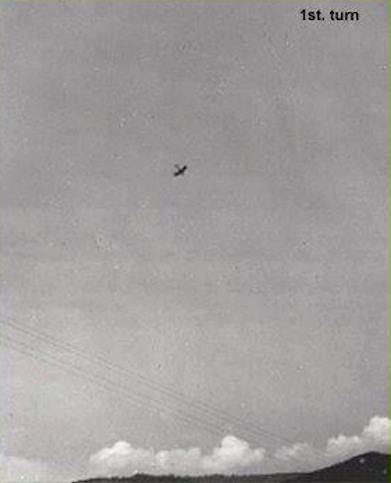

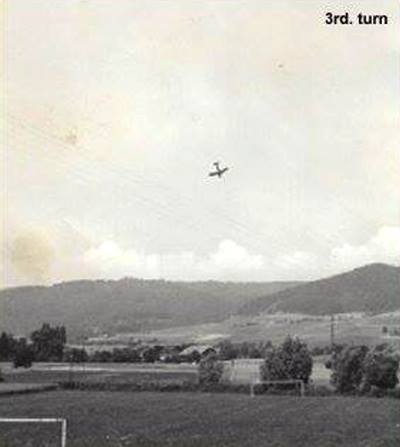

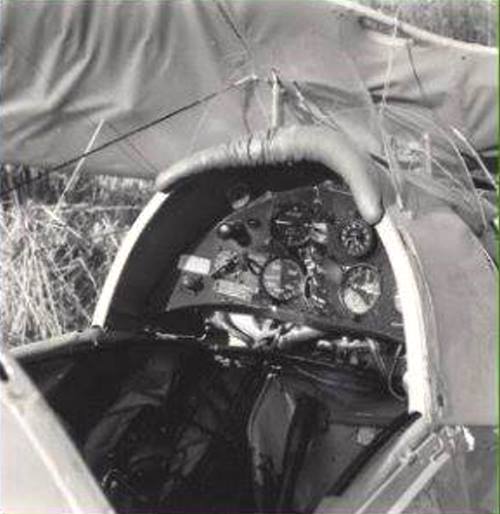

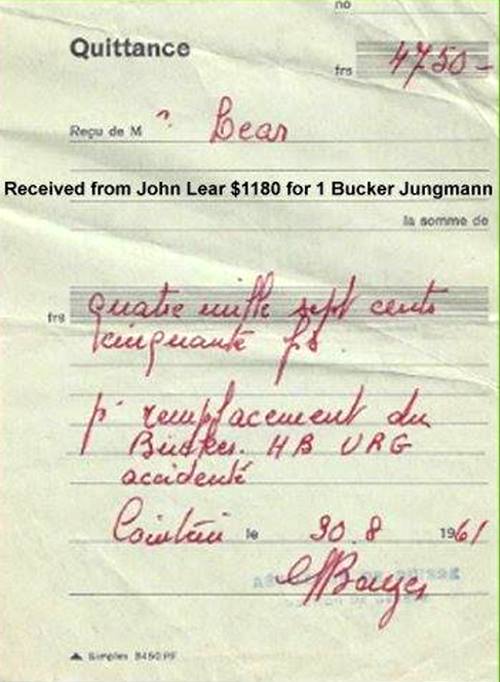

February 1 2018 at 10:42am Coming soon: Deadly Mistress originally published by Air Trails winter of 1976. Robyn McCoy: So many pilots get in over their head ! John Lear: Thanks Robyn. I was wondering what happened. Robyn McCoy: John, hope this wasn't your crash in Germany.. John Lear: Robyn McCoy Yes Robyn McCoy it was and it was in Switzerland. You can see the wheat field I crashed in, Its just behind he soccer field. Le Rosey is located in the Swiss town of Rolle. Ask Sam, he was there. Robyn McCoy: John, sorry for my comment ! John Lear: Robyn McCoy No problem It was accurate. Love you. Gerard Gallagher: Stick & rudder, Seat of the pants flying. Where heroes are born. Daryl Brann: What fun that must have been to fly! Not much left of her. Your will to live and survive that crash brings us all pleasure through these stories. John Lear: Daryl Brann C'mon Alice. I suspect you are reading FB. Tell the folks what fun I was! John Lear Posted Feb 08 2018 DEADLY MISTRESS The Story of my Airplane Crash June 24, 1961. I was 18 years old and as dumb as they come. In the two seconds of flight that remained for me before impact there was scarcely time to realize that, but for a miracle I would soon be dead. I can remember using that two seconds to plan a cover story for what had happened. The thought process near death is somehow vastly speeded up and I still (optimistically) planned to recover from the spin with maybe only the loss of the landing gear and I was already planning a 'gear gone'; landing back at Geneva's grass strip. I didn't actually remember the second of crashing until three years later when I had a total recall under unusual circumstances. I was in a passenger seat next to the window of a Swissair DC-8 on final approach to Geneva, over approximately the same area that I had crashed. At about 1500 feet a little higher than the altitude from which I had started the near fatal spin I vividly recalled the crash including the impact and the enormous weight that threatened to cave in my back. Both straps of the shoulder harness snapping allowing my face to bury into the instrument panel. I jerked violently in the passenger seat at the memory as it had been so real, so accurate and so momentary. Never again would I experience such a flashback. The little yellow Bucker HB-URG and I had started the day in an early morning takeoff for a flight to Berne, Switzerland. I had gotten the green light from Geneva's Cointrin control tower (my craft had no radio) and had departed the grass runway 23. Flying the Jungmann was a delight in simplification compared to the Beechcraft and Lodestar that I flew as copilot for my Dad's company. Directional control for takeoff was a piece of cake and handling in the air was both harmonizing and responsive. As I banked to the right for a downwind departure the big blue Jura range of mountains stretched from southwest to northeast on my left  Within a radius of 30 miles from my present position I had escaped serious injury from a potential aircraft accident no less than twice in the past month. Yet I didn't feel like a dangerous pilot. Nobody ever does. After all, I had a Commercial license with Instrument rating, single and multi-engine endorsements and a type rating in the Lockheed L-18 Lodestar, a heavy twin-engine WWII transport. Further, I had successfully completed the Swiss Aerobatic Rating course and now had the coveted Vol de Virtuosite. And I hadn't hesitated to point this all out early that summer morning when the dispatcher for the Aero Club of Geneva, to whom the Bucker belonged, informed me that the little craft was restricted to local flight only, due to the recent loss of their first Jungmann and that the proposed trip to Berne he prohibited. After much pompous oratory on the subject of pilot qualifications, as compared with those of the pilot who had wrecked the previous Bucker. I cowered the dispatcher into releasing us for the flight, much to his continued consternation. Barely one month before the Aero Club had lost their little Bucker Jungmann in a forced landing near the Saleve mountain to the east of Genevas airport. The beautiful little trainers were hard to come by and a few of the last remaining aircraft were in the hands of the Swiss Air Force who released them piecemeal to the to the Swiss Aero Clubs. Having had their first replaced it was unlikely that they would receive another. Hence the conservative flight restrictions.  It was June 24, 1961 and the Mt. Blanc, to the east, stood out clearly for the season. Between myself and the continents highest peak rose the curiously pointy topped mountain La Mole. The 108-hp Hirth climbed us rapidly in the fresh cool, Swiss air. Further to the left of the Massif du Mt. Blanc the Dents du Midi, another range of formidable Swiss peaks, rose in the north east. The route I was to follow took me over the towns of Nyon, Rolle and Lausanne, all on the west shore of the Lake of Geneva or 'Lac Leman'. In spite of my warm suede jacket, gabardine pants and the long white scarf (on which I was about to choke), I found it too cold at my selected cruising altitude of 3000 meters (10,000 feet) and started a descent over the Rochers de Naye peaks at the north end of the lake. A huge Castle lay nestled in those peaks above Montreau, belonging to he Moral Re-Armament group. I dropped down to about 1000 meters (3000 feet) on the other side of the range, and sped along the warm green countryside, waggling my wings at the farmers and generally hamming it up. At Berne I entered the traffic pattern and landed to the north on the long right strip. As I parked the airplane I looked around for a suspect to prop me when I got ready to go. (the Bucker has no internal engine starter and required someone to pull he propeller through to get it running. I pulled the mixture, switched off the mags, popped open the side panels and climbed out.  I walked out the minor stiffness of the hour and fifteen minute flight and went over to hitch a ride downtown. After a 2 hour visit to Berne which involved getting some information for a friend on Swiss regulations governing the licensing of foreign airmen. I proceeded back to the field and talked one of the locals into propping the Bucker. I was now anxious to get back to Geneva to do those things which are most important to 18 year olds on a warm summers day. With women. I flew a direct course back to Geneva at 2500 meters (about 7000 feet). A haze had formed in the meantime and the Mt. Blanc poked up out of he top. My course took me directly over the village of Rolle which is the site of the 'School for Kings' Le Rosey, a boarding school to which I had been sent by my father who told me, I would make the kind of friends that will be useful to me in the future.  Fifty seven years later I have met 2 or 3 of my former classmates 2 of whom asked me for a job. I decided that an impromptu display of my aerobatic prowess would be in order and as I had received my Vol du Virtuosite in the same aircraft, a Bucker 131 Jungmann and had no lack of confidence for the proposed performance. In Switzerland, in those days, the performance of aerobatics required a special license that was issued by the Swiss Federal Air Office. To get the certificate one had to successfully complete a course in aerobatics with a certificated instructor and then demonstrate a series of two flights, each with a set of required maneuvers to be completed in fifteen minutes. These flights were monitored by a Swiss Federal Air Expert (equivalent to an FAA inspector) who graded the exhibition. If he felt that your display measured up to the strict standards of the Vol de Virtuosite the license was then issued. But even then aerobatics were only permitted directly over the airport at specific times, and when traffic was neither inbound or outbound for a period of 30 minutes. During 1961 at Geneva Airport these periods were few and far between.  I applied carburetor heat and glided down in a long circling dive. The dormitory to which I would give the grandstand presentation was oriented north and south and I planed to align the exhibition along a parallel course 100 meters to the west. I had been out of school for about 6 months so still had plenty of friends who knew that a low flying airplane in that area was probably me. The Twin Beech N34L or “34 Lima Beam” as it was affectionately known had been the aircraft in which I had escaped a probable accident, one of the two incidents that had occurred in the previous month. During the Paris Air Show that year in which the Lear Company had a 'chalet' and was trumpeting the Lear Jet (nee SAAC 23). Pilot Bob Richardson and myself has been doing some extensive shuttling of personnel between Geneva, Paris and London. Bob, who was a knowledgeable and experienced corporate pilot was always pilot in command and I always rode shotgun. We had flown together all that winter around Europe in and out of the ice and snow and foul weather in old 34 Lima Bean until we had developed a high degree of coordination in working together. On one particular mission toward the end of the show we were dispatched to Geneva to then proceed to Altenrhein to pick up the recently finished scale model of the Lear Jet and deliver it to the Paris Air Show. Time was of the essence as the show ended in a couple of days and display time short.  We arrived at Geneva in marginal weather and checked Altenrhein. They were reporting measured ceiling 200 overcast ˝ mile visibility in moderate rain with heavy icing reported at 4000 feet. Zurich was reporting the same. Bob, the sensible fellow that he was scrubbed the flight. I, realizing the importance of getting the model airplane to Paris, decided to take the flight myself. Bob wished me good luck and headed to downtown Geneva. I filed the flight plan, walked out in the rain and climbed into 34 lima bean. I closed the airstair, pull-up door, walked up the aisle and settled into the left seat. This would be my second solo flight in the Twin Beech. I started the engines and requested taxi, 'IFR to Altenrhein'. Altenrhein incidentally had no published approach, and the flight to would be a matter of proceeding to an intersection near the airport and, if he field was not in sight then to the alternate of Zurich. There was however, a small non-directional beacon nearby on which I planned to make a letdown. After a thorough runup I requested take off clearance and was cleared direct HEW (Gland NDB) on course, to maintain 7000 feet, moderate icing reported at 4000 feet. Off I went climbing into the muck and the murk.  The first thing I concluded as I climbed into the clouds was that to keep out of the ice I would have to stay below the overcast. But this naturally meant canceling IFR as the MEA's (minimum enroute altitude) were higher than the ceiling. So I canceled IFR and proceeded VFR up as far as Lausanne. Around Lausanne it became quite obvious that I was neither capable nor experienced enough for continued flight in that direction. I was attempting to maintain VFR in deteriorating weather, and ice had started to build up on the wings. Funny. Ice never bothered me when Bob was in the left seat....there was something about ice when I was alone... I made a slow right turn out over Lake Geneva and called Geneva approach control trying to control the panic in my voice. Geneva came in loud and clear and vectored me to the ILS which was a short distance away.. I made the approach and landed without further incident. Npne the wiser. The whine of the Bucker's engine had brought my former claqssmates to the windows of the 3 story dormitory and an adequate crowd, to my standards, had gathered for the commencement of the exhibition. I gave a little thought to the fact that this exercise would be wholly illegal but in my youthful exuberance disregarded all common sense. I planned a performance modified from that in the rating exhibition. Starting at 3000 ft. I would do a slow roll to the right on the first pass, then reverse course and do a roll to the left. Then reverse course again and perform a loop into a hammerhead stall to the right followed by a loop and hammerhead stall to the left. The final maneuver for this abbreviated aerobatic demonstration would be a three turn spin. Sensational!  I lowered the nose and picked up speed. Down, down, down over the green Swiss countryside then back pressure and a roll to the right. I looked over the side and down at the crowd not very far away. I could not see the smiles or hear the cheering. A left turn and I picked up speed again. Back pressure, nose above the horizon Then another roll, this one to the left, my better side. I glanced at the altimeter. I cannot remember exactly but it was calibrated in meters and must have read close to 1300 meters (3900 feet). Another left turn now facing south with the Jura range on my right. The west side of the Jura Range, near the village of Morez had been the site of my second near disaster in the past month. The final warning. A very colorful aviation magazine had sprung up in Europe in the summer of 1960 and its owner/publisher Bob Jackson, a dynamic and interesting American, was championing for the rights of the private aviator in Europe. The magazine, 'Private Pilot' was in 4 color, included some very interesting stories, and was full of barbed comments on Europes aviation bureaucracy. Bob was then flying his brand new Debonaire Beechcraft, and since he was not instrument rated, made it a point to always take along another pilot with that particular rating. It so happened that I was standing around on the final day of the Paris Air Show that year and volunteered to fly with Bob back to Geneva in his Debonaire. The weather was crummy and we took a cab from Le Bourget to Tousous-le-Noble airfield in the southwest of Paris, where the aircraft was parked.  As we fired up and readied for take off we heard a lot of excited chatter on Paris control frequency, something about a crash. We were later to find out out that it had been a U.S. Air Force B-58 Hustler that had crashed while executing a slow roll for the crowd on its final pass. We worked our way out of the control zone and managed to make it VFR all the way past Dijon and right up until the Jura which had created a huge cloudy weather barrier just west of Geneva. Our problem was this: we were on a VFR flight plan and could no longer continue in the direction of Geneva without climbing over the mountains. Since a climb would put us in the clouds we'd need a clearance from Air Traffic Control to an altitude at which we could reach Geneva. I was for getting a clearance and continuing on, Bob was for calling it a day, flying back to Dijon and spending the night. I used persuasive arguments concerning the expensive radio equipment with which the airplane was equipped and my own mastery of the instrument flight etc. Bob's counter argument was he felt that someday he would die in an airplane and he didn't want it to be today. I finally talked him into my plan and we proceeded to climb up through the scud. I figured if we could get up to around six or seven thousand feet we could talk to Geneva and get a clearance, as the MEA (minimum enroute altitude) was 7000 ft. We were on solid instruments at 4500 feet and Bob became very worried not to say downright panicked. I can't say, looking back, that it was unjustified. At about 7000 feet in the climb he issued an ultimatum that either I descend back down to VFR conditions or that he would attempt to do it himself. Realizing that the former would be safer I descended back down and we broke out in VFR conditions and continued back to Dijon where we spent the night. The next day we proceeded VFR to Geneva and we passed over the Jura in clear, blue skies. I wondered what would have been the consequences of continued flight yesterday.  Today I was flying the Bucker and built up some speed in another shallow dive. Up into a loop, hanging on the top, then down the other side and up into a hammerhead stall to the right, hanging there...until all upward motion stopped..right rudder..easy, pointed vertically straight down. Altimeter indicating about 800 meters. Now up into another loop. At the moment of impact which was not until another 2 or 3 minutes away, I had accumulated exactly 448 hours of flight time of which 167.4 were with an instructor, 233.3 solo, 26 at night, 208.2 cross country, 67.7 link (the old type of flight simulator) and 46.6 actual instrument (in the clouds). This flight time falls well within the most 'dangerous' period of flight, statistically for a pilot, according to the NTSB (National Transportation Safety Board) figures. In between three and five hundred hours. If a pilot can make it through that period without accident he is then statistically 'safe' until about 3,000 hours where there is another accident 'high'. After that he is 'safe' until over 10,000 hours where there is yet another 'peak' of accidents. With a grand total of 150 hours a year before, I had once come back from a solo flight to the school where I had learned to fly, Lind Flight Service, at Santa Monica (Cloverfield) airport. I proceeded to brag about about the flight across the Pacific Ocean wave tops with the altimeter reading less than zero feet altitude. Mel Lind, the owner looked at me patiently and said, “John, one of these days you're going to bust your ass!~” Truer words were never spoken. Today, over the Swiss countryside I was pointing down out of the second loop and climbing into another hammerhead stall, this one to the left. While pulling out of the ensuring dive I glanced over the side of the cockpit and also looked at the altimeter which said 600 meters. I planned to start the final maneuver, a three turn spin at one thousand feet above the ground which would give me 200 feet of clearance after recovery and pullout at the bottom. Entirely adequate for an experienced aerobatic pilot, which I was not. As I pulled up into the climb to 700 meters altitude I racked the obedient little Bucker into an 'over the top' spin entry. I remember shouting “Yahoooo” in the excitement of the moment. I counted the turns: first turn. Among other things I had forgotten was probably the most important and that was the elevation of the terrain which was 1400 feet about 450 meters. I didn't realize I had about 100 feet less than I needed to safely complete the spin and pull out without hitting the ground. Second turn: I remember looking out at a barn that was going by and thinking gosh I look low. Beginning the third turn the inevitability of the crash was forming in my mind. But I still had hope... A sequence of pictures was taken by a former classmate Wes Holden, actor Bill Holdens son. With fast reflexes he shot the first turn, second turn, third turn and final shot of he aircraft about 3 feet from impact with the ground, aircraft pointed down in a 30 degree angle with the terrain. The Swiss Federal Air office had had the negatives enlarged to determine if the spin was intentional, which of course it was. They also pointed out the fact that at the beginning of the third turn when a crash was now inevitable, that the rudder and ailerons were still hard over in spin configuration. Which of course is correct because it was only at the beginning of the the third turn that I began to realize the trouble I was in. At the point just before impact the rudder and ailerons where returned to the neutral position along with the elevators but far, far too late. Half way through the third turn I remember seeing the barn again that appeared just a little lower than my altitude. I was about 50 feet from the ground. In the split second before impact I still had hopes of recovery because I can remember trying to concoct a plausible story for how I had wiped out the landing gear which is all the damage I could foresee in my boundless optimism, as I pulled up after scraping the ground. I would proceed to Cointrin and make a gear-less belly landing on the grass strip. The actual crash was instantaneous and was wiped from my memory. Or so I thought. I had a total recall about 3 years later. The tremendous force on my back, my shoulders snapping both shoulder harnesses, my face going through the instrument panel. My face on its way through the altimeter and airspeed indicator broke both sides of my jaw, and knocked out 4 of my front teeth and caused severe and numerous facial lacerations. This could have been much worse had it not been for he initial restraint of the well-secured shoulder harnesses which, before both straps finally broke, cushioned my forward movement. The shoulder harness straps were later snap tested to 3000 pounds, approximately 22 Gs. The small metal rods that serve as rudder pedals on the Jungmann rammed up and crushed both heels bones, joints and ankles with a force that additionally broke both legs in 3 places. Part of the instrument panel had been forced into and crushed my neck. The airplane moved exactly 6 feet forward on the ground. Due in part to the fact that the airplane had been refueled in Berne and had almost a full fuel tank, there was no fire. (not enough ogygen to support a flame.) I was unconscious and don't remember my classmates pulling me from the airplane. Nor do I remember the ambulance ride into Rolle where it was decided that proper medical attention could only be rendered in Geneva. Nor the ambulance ride into Geneva, about an hour bumpy ride. I don't know where or when the tracheotomy was performed and breathing pipe inserted into my throat. I do clearly remember floating above my body as the ambulance bumped along the road to Geneva. Every bump worsened my condition but I never felt a thing. I looked down at my body and made an assessment: I'm not going to make it. My body is too badly damaged. I don't remember any of the 5 hour operation in which doctors could only perform the barest medical necessities for my condition or the next three days in a coma.. My ankles had compound fractures and bones wee sticking out in all directions. Reconstructive surgery was not an option at this point. The first thing I remember was waking up in the hospital and feeling the restraints that were attached to my arms and legs preventing any movement. There were seven intravenous attachments and other hoses which occupied every possible body cavity. The restraints were secure to be sure that none of the hoses, pipes, tubes and needles slipped out. The windows in the intensive care room appeared to be heavily barred and was typical of old Geneva building construction. But I thought “ They've put me in a looney bin and they're not going to give me a chance to explain how I fucked up.” I then began to conjure up an excuse for the disaster, other than, of course my own incompetence. But due to the effects of heavy doses of Demerol, the importance of this seemed to vanish into thin air. As a matter of fact when the Federal Air Office investigators showed up several days later, after I was out of intensive care, but still under the effects of the pain killers I cheerfully told them the exact truth. The little yellow Bucker Jungmann had been damaged beyond repair, but fortunately, the Swiss Air Force had sold the Geneva Aero Club yet another replacement for which I paid the exact and total amount of $1180.00. When I was still in intensive care my Dad came in and asked how I was. To talk I had to put my finger against the tube in my throat for sound to come out. I said. “I'm ok Dad.” He said, “Good. Anybody that would do such a god damned stupid thing as that isn't going to work for my company, you're fired.” His outrage was not unexpected because the day I crashed was his birthday and all of Geneva's movers and shakers were coming to our house to celebrate. Many had already heard about my crash and didn't come. Those who arrived and then heard were extremely apologetic and started to leave. Dad told them that I only had a few scratches and that I would be ok and that the party should go on. Most of them refused to stay shocked at Dads attitude. I contracted gangrene in one of the open wounds in my ankle and I was shipped to the Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico where Dr. Randy Lovelace cured the gangene and helped with my rehabilitation. Many of you may know that Dr. Lovelace was an Air Force surgeon at Wright-Patterson and shortly after the Roswell crash was sent to Albuquerque, his home town, to build the Lovelace Clinic where most of the alien bodies that were recovered were shipped. The Lovelace Clinic was specifically built as a cover for that operation. Dr. Love lace was also the Chief Medical Officer for all of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo astronauts. I learned how to walk again in about 6 months. I flew a very successful aviation career that lasted 38 years. I retired in April of 2001 with !9,470 hours. As of February 2018 I remain the pilot with the most FAA Certificates. Yes, I still have pain but control it successfully with Kratom. I have 4 daughters and on May 22 will celebrate 47 years of marriage. John Lear |

|

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | |

|

|