Zhangzhung Kingdoms

..

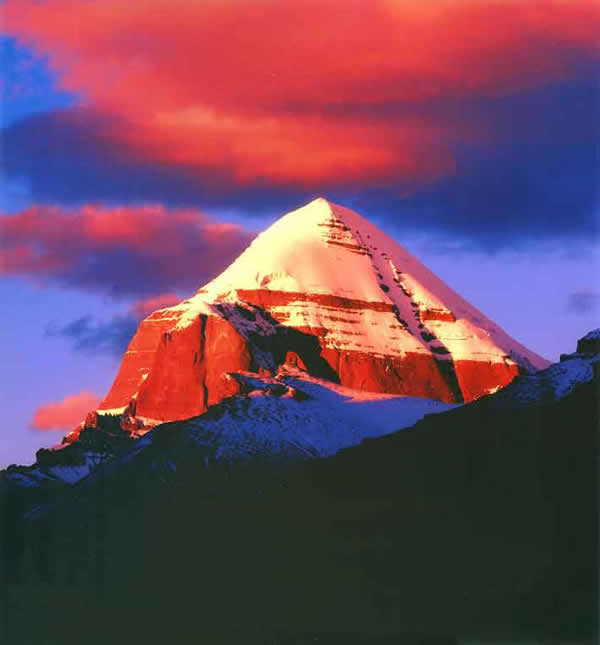

Mount Kailash, Courtesy

chinawesttour.com

Zhang Zhung, Shang Shung, or Tibetan Pinyin Xang Xung,

was an ancient culture of western and northwestern

Tibet, which pre-dates

the culture of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet. Zhang Zhung culture is associated

with the Bön religion, which in turn, has influenced the philosophies

and practices of Tibetan Buddhism. The Zhang Zhung are mentioned frequently

in ancient Tibetan texts as the original rulers of central and western

Tibet. Only in the last two decades have archaeologists been given access

to do archaeological work in the areas controlled by the Zhang Zhung.

Recently, a tentative match has been proposed between

the Zhang Zhung and an Iron Age culture now being uncovered on the Chang

Tang plateau of northwestern Tibet.

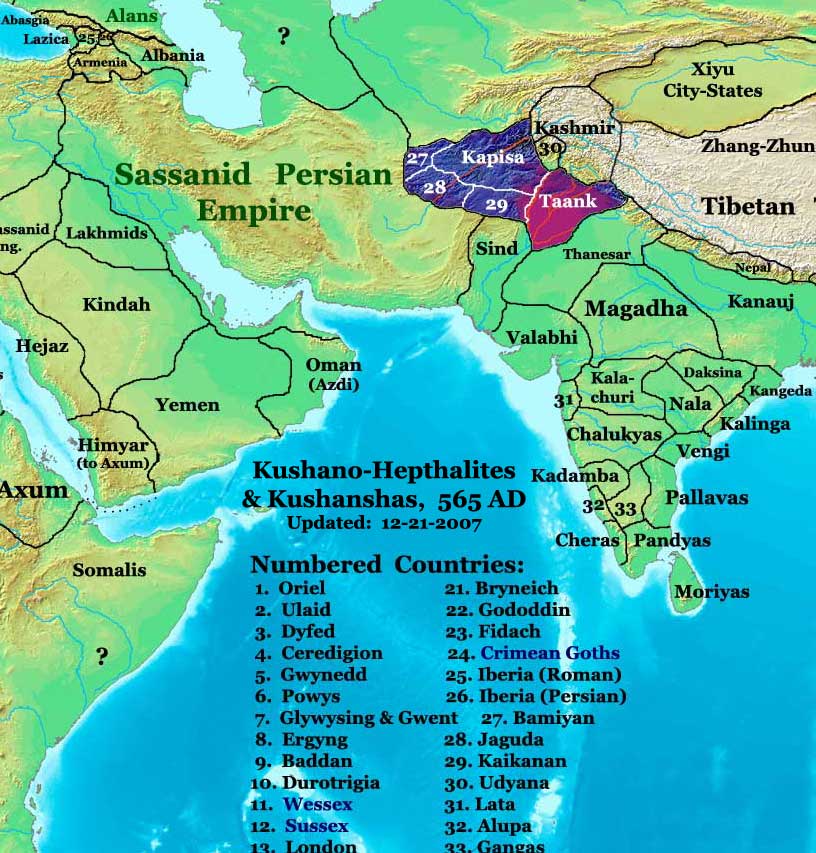

Extent of the Zhang Zhung Kingdoms

..

The Kushano-Hephthalite Kingdoms in 565 AD

According to Annals of Lake Manasarowar (Lake

Manasarovar), at one point the Zhang Zhung civilization consisted of 18

kingdoms in the west and northwest portion of Tibet. The Zhang Zhung culture

was centered around sacred Mount Kailash and extended west to Sarmatians

and present-day Ladakh & Baltistan, southwest to Jalandhar, south to

the Kingdom of Mustang in Nepal, east to include central Tibet, and north

across the vast Chang Tang plateau and the Taklamakan Desert to Shanshan.

Thus the Zhang Zhung culture controlled the major portion of the "roof

of the world".

Tradition has it that Zhang Zhung consisted "of three

different regions: sGob-ba, the outer; Phug-pa, the inner; and Bar-ba,

the middle. The outer is what we might call Western Tibet, from Gilgit

in the west to Dangs-ra khyung-rdzong in the east, next to lake gNam-mtsho,

and from Khotan in the north to Chu-mig brgyad-cu rtsa-gnyis in the south.

The inner region is said to be sTag-gzig (Tazig) [often identified with

Bactria], and the middle rGya-mkhar bar-chod, a place not yet identified."

While it is not certain whether Zhang Zhung was really so large, it is

known that it was an independent kingdom and covered the whole of Western

Tibet.[1][2]

The capital city of Zhang Zhung was called Khyunglung

(Khyunglung Ngülkhar or Khyung-lung dngul-mkhar), the "Silver Palace of

Garuda",

southwest of Mount Kailash (Mount Ti-se), which is identified with palaces

found in the upper Sutlej Valley.[3]

The Zhang Zhung built a towering fort, Chugtso Dropo,

on the shores of sacred Lake Dangra, from which they exerted military power

over the surrounding district in central Tibet.

The fact that some of the ancient texts describing

the Zhang Zhung kingdom also claimed the Sutlej valley was Shambhala, the

land of happiness (from which James Hilton possibly derived the name "Shangri

La"), may have delayed their study by Western scholars.

History of the Zhangzhung

Paleolithic findings

Pollen and tree ring analysis indicates the Chang Tang

plateau was a much more livable environment until becoming drier and colder

starting around 1500 BC. One theory is that the civilization established

itself on the plateau when conditions were less harsh, then managed to

persist against gradually worsening climatic conditions until finally expiring

around 1000 CE (the area is now used only by wandering nomads). This timeframe

also corresponds to the rise of the Tibetan kingdoms in the southern valleys

which may also have contributed to the decline of the plateau culture.

Iron Age culture of the Chang

Tang - the Zhang Zhung?

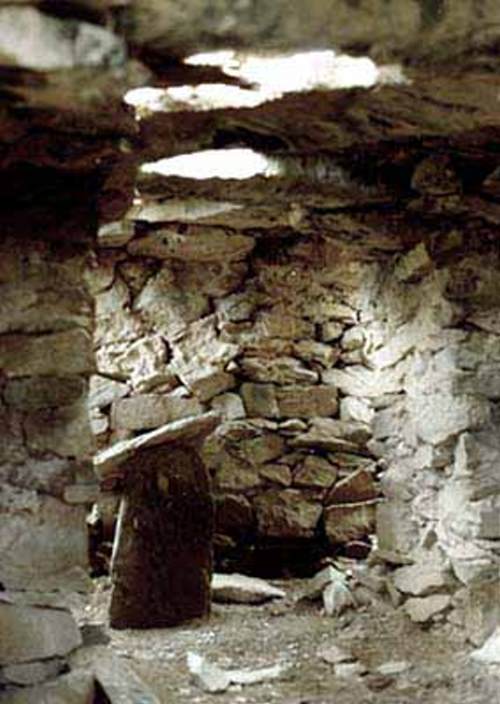

Recent archeological work on the Chang Tang plateau

finds evidence of an Iron Age culture which some have tentatively identified

as the Zhangzhung. This culture is notable for the following characteristics:

-

a system of hilltop stone forts or citadels, likely used

as a defense against the steppe tribes of Central Asia, such as the Scythians

-

burial complexes which use vertical tombstones, occasionally

in large arrays, and including up to 10,000 graves in one location

-

stone temples located in the mountains adjacent to the

plains, characterized by windowless rooms, corbelled stone roofs, and round

walls

-

evidence of a stratified social structure, as indicated

by royal or princely tombs

-

petroglyphs which shows the culture was a warrior horse

culture

These characteristics more closely match the Iron Age

cultures of Europe and the Asian steppes than those of India or East Asia,

suggesting a cultural influence which arrived from the west or north rather

than the east or south.

The Conquest of Zhangzhung

There is some confusion as to whether Central Tibet

conquered Zhangzhung during the reign of Songtsän

Gampo (605 or 617? - 649) or in the reign of Trisong Detsän (Wylie:

Khri-srong-lde-btsan), (r. 755 until 797 or 804 CE).[4]

The records of the Tang Annals do, however, seem to clearly place these

events in the reign of Songtsän Gampo for they say that in 634, Yangtong

(Zhang Zhung) and various

Qiang tribes "altogether submitted to him." Following

this he united with the country of Yangtong to defeat the 'Azha or Tuyuhun,

and then conquered two more tribes of Qiang before threatening Songzhou

with an army of more than 200,000 men. He then sent an envoy with gifts

of gold and silk to the Chinese emperor to ask for a Chinese princess in

marriage and, when refused, attacked Songzhou. He apparently finally retreated

and apologised and later the emperor granted his request.[5][6]

Early Tibetan accounts say that the Tibetan king and

the king of Zhangzhung had married each other's sisters in a political

alliance. However, the Tibetan wife of the king of the Zhangzhung complained

of poor treatment by the king's principal wife. War ensued, and through

the treachery of the Tibetan princess, "King Ligmikya of Zhangzhung, while

on his way to Sum-ba (Amdo province) was ambushed and killed by

King Srongtsen Gampo's soldiers. As a consequence, the Zhangzhung kingdom

was annexed to Bod [Central Tibet]. Thereafter the new kingdom born of

the unification of Zhangzhung and Bod was known as Bod rGyal-khab."[7][8][9]

R. A. Stein places the conquest of Zhangzhung in 645.[10]

Revolt of Zhang Zhung in 677

CE

Zhang Zhung revolted soon after the death of King

Mangsong

Mangtsen or Trimang Löntsän (Khri-mang-slon-rtsan, r. 650-677), the

son of Songtsän Gampo, but was brought back under Tibetan control by the

"firm governance of the great leaders of the Mgar clan". [11]

The Zhangzhung language

A handful of Zhangzhung texts and 11th century

bilingual Tibetan documents attest to a Zhangzhung language which was related

to Kinnauri. The Bönpo claim that the Tibetan writing system is derived

from the Zhangzhung alphabet, while modern scholars consider the question

open. Given the rarity of text samples, another possible explanation is

that the 11th century Bönpo, struggling for legitimacy as Kadampa and

Nyingmapa sought to marginalize Bön, resorted to creating an artificial

ancient writing system.

A modern Kinnauri language called by the same name

(pronounced locally Jangshung) is spoken by 2000 people in the Sutlej Valley

of Himachal Pradesh who claim to be descendants of the Zhangzhung.[12].

Zhangzhung culture's influence

in India

It is noteworthy that the Bönpo tradition was founded

by a buddha like figure named Tonpa

Shenrab Miwoche[13], whose teachings

are similar in scope to the teaching espoused by the historical

Buddha.

Bönpos claim that Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche lived some 18,000 years ago, and

visited Tibet from the land of Tagzig

Olmo Lung Ring, or Shambhala. Bönpos also suggest that during this

time Lord Shenrab Miwoche's teaching permeated the entire subcontinent

and was in part responsible for the development of the Vedic religion.

An example of this link is that Mount Kailash, as the center of Zhang Zhung

culture, is also the most sacred mountain to Hindus. In turn, Buddhism

evolved from the spiritual teachings of the Vedic religion. As a result,

the Bönpos claim that the much later teaching at least indirectly owes

its origin to Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche.

See also

Footnotes

-

Karmey, Samten G. (1979). A General Introduction to

the History and Doctrines of Bon, p. 180. The Toyo Bunko, Tokyo.

-

Stein, R. A. (1972). Tibetan Civilization. Stanford

University Press, Stanford, California. ISBN

0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN

0-8047-0901-7.

-

Allen, Charles. (1999). The Search for Shangri-La:

A Journey into Tibetan History. Abacus Edition, London. (2000), pp.

266-267; 273-274. ISBN

0-349-11142-1.

-

Karmey, Samten G. (1975). "'A General Introduction to

the History and Doctrines of Bon", p. 180. Memoirs of Research Department

of The Toyo Bunko, No, 33. Tokyo.

-

Lee, Don Y. (1981). The History of Early Relations

between China and Tibet: From Chiu t'ang-shu, a documentary survey,

pp. 7-9. Eastern Press, Bloomington, IN.

-

Pelliot, Paul. (1961). Histoire ancienne du Tibet,

pp. 3-4. Librairie d'Amérique et d'orient, Paris.

-

Norbu, Namkhai. (1981). The Necklace of Gzi, A Cultural

History of Tibet, p. 30. Information Office of His Holiness The Dalai

Lama, Dharamsala, H.P., India.

-

Beckwith, Christopher I. (1987). The Tibetan Empire

in Central Asia, p. 20. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Fourth printing with new afterword and 1st paperback version. ISBN

0-691-02469-3.

-

Allen, Charles. The Search for Shangri-La: A Journey

into Tibetan History, pp. 127-128. (1999). Reprint: (2000). Abacus,

London. ISBN

0-349-11142-1.

-

Stein, R. A. (1972). Tibetan Civilization, p. 59.

Stanford University Press, Stanford California. ISBn 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth);

ISBN

0-8047-0901-7.

-

Beckwith, Christopher I. The Tibetan Empire in Central

Asia. A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks,

Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, 1987, Princeton: Princeton

University Press. ISBN

0-691-02469-3, p. 43.

-

Ethnologue

14 report for language code:JNA

-

http://www.ligmincha.org/bon/founder.html

References

-

Allen, Charles. (1999) The Search for Shangri-La: A

Journey into Tibetan History. Little, Brown and Company. Reprint: 2000

Abacus Books, London. ISBN

0-349-111421.

-

Bellezza, John Vincent: Zhang Zhung. Foundations of

Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the

Monuments, Rock Art, Texts, and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland.

Denkschriften der phil.-hist. Klasse 368. Beitraege zur Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte

Asiens 61, Verlag der Oesterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien

2008.

-

Hummel,

Siegbert. (2000). On Zhang-zhung. Edited and translated by Guido

Vogliotti. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. Dharamsala, H.P., India.

ISBN

81-86470-24-7.

-

Karmey, Samten G. (1975). A General Introduction to

the History and Doctrines of Bon. Memoirs of the Research Department

of the Toyo Bunko, No. 33, pp. 171-218. Tokyo.

-

Stein, R. A. (1961). Les tribus anciennes des marches

Sino-Tibétaines: légends, classifications et histoire. Presses Universitaires

de France, Paris. (In French)

External links

|